Hima Anjar and the Umayyad ruins – Natural and Cultural values

Anjar, West Beqaa, Lebanon

Ghassan Ramadan-Jaradi1, Bassam Al Kantar2, Assad Serhal3 and Bassima Khatib4

1) grjaradi@hotmail.com, 2) bassam.kantar@gmail.com, 3) aserhal@spnl.org, and 4) bkhatib@spnl.org

Address of the four authors: SPNL | Society for the Protection of Nature in Lebanon. Horsh Kayfoun، Luc Hoffmann Hima Center، Itani, Kayfoun, Lebanon

Phone: +961 5 271 041

Date of Publication: SEPTEMBER 2024

ABSTRACT

The Hima Anjar case study is a very good example of the harmonization of the cultural heritage with the conservation of nature in Lebanon and the Middle East, based on the Hima, an Islamic type of community conserved area revived by the Society for the Protection of Nature in Lebanon, using intercultural and interreligious approaches. The site includes a complex of wetlands, which are considered a Key Biodiversity Area, specially for a number of bird species, as well as an outstanding archaeological site: the Islamic Anjar Castle, an UNESCO Cultural World Heritage Site. The Armenian local community, descendents of past century refugees, has played a significantly positive role, inspired by Christian religion and values. A significant part of the conservation management is under the responsibility of Homat al-Hima, volunteers from the local community, working in close collaboration with the concerned national and local institutions.

Key Words: Anjar, UNESCO, Nature, culture, heritage, Hima, wetland.

INTRODUCTION

Hima means ‘conserved place’ in Arabic; it is a community-based approach used for the conservation of sites, species, habitats, and people in order to achieve the sustainable use of natural resources. It originated from more than 1,500 years ago where it was spread along the Middle East as a “tribal” system of sustainable management of natural resources (Gari, 2006). It was often applied as a system for organizing, maintaining and utilizing rangelands in a way fitting with ecosystems and local practices. With the emergence of Islam, its function changed; it became a property dedicated to the well-being of the whole community around it. Tribes had their own Hamas with the permission of the state, and acted as self-government in the absence of state control (Gari, loc. cit.). Hima management and decisions are made by the local communities themselves. The Society for the Protection of Nature (SPNL) is reviving the hima approach in collaboration with municipalities to promote the conservation of Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBBAs) and the sustainable use of natural resources. So far, SPNL has established 26 Himas in Lebanon focusing on sustainable hunting, fishing, grazing, farming and the use of water resources.

The major international recognition of the Hima approach was through the IUCN’s Motion adopted during the 5th IUCN World Conservation Congress of Jeju (IUCN, Motion 122, 2012). Hima has been adopted as a Category IV Protected Area in the IUCN System within the draft law for protected area management in Lebanon.

This case study discusses the Anjar (Figure 1) hima which includes outstanding natural, and cultural values, focusing on the community-based management

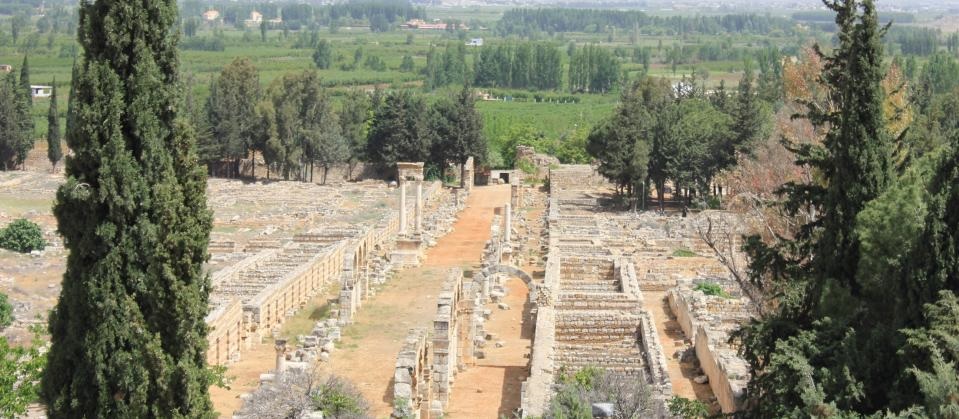

Figure 1: Western parts of Anjar ruins (Source: Berj Tumberjian).

Figure 2: Eastern parts of Anjar ruins (Source: ngno).

Natural values

Anjar wetland is a flood plain (Figure 3) including a complex of permanent rivers (Shamsine and Ghazal rivers), seasonal rivers and streams, which provide habitat for different species of flora and fauna, some of them globally threatened, as the breeding European Turtle Dove (Streptopelia turtur) and Syrian Serin (Serinus syriacus) bird species (BirdLife RedList, 2020b; Ramadan-Jaradi et al., 2008, 2020). Anjar’s eastern communal lands (256 ha), including the lower slopes of the Anti-Lebanon mountain, have been declared a potential Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBBA) by SPNL in Lebanon in 2005, and approved as IBBA, category A1 by BirdLife International in 2008 (BirdLife, 2008).

Figure 3: Swamps of Anjar. (Source: Alfred Ina).

In 2008, Anjar was also declared a Hima by the municipal council in collaboration with SPNL covering the IBBA and the remaining parts of Anjar (Serhal et al. 2010), including the Anjar residential area because the backyard of nearly every house with conifer trees hosts the globally threatened breeding Syrian Serin (Ramadan-Jaradi pers. obs.). In 2016, Hima Anjar was nominated as a Key Biodiversity Area and its Ramsar Information Sheet (RIS) was submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat in 2017 with the hope to be soon nominated as a Ramsar Site. SPNL will follow up this RIS to confirm that the nomination is in progress.

SPNL, the primary responsible NGO for the Hima/IBBA Anjar, believes that local community has an important role in the improvement of conservation actions. Since youth represents a high numerical percentage, and are agents for change of the future, SPNL decided to develop the capacities of youth to support the conservation of Himas, including Hima Anjar. In 2014, SPNL established the Homat Al-Hima fund in Qatar to serve this purpose in the region. Homat Al-Hima is an Arabic slogan widely used in the region to recognize individuals acting as Hima guardians and heroes (Serhal, 2016). Homat Al-Hima at Anjar are motivated, well trained and equipped young persons, working under the direct supervision of the local elected authority. They feel themselves as the owners of the Hima and they believe that part of their duties is to disclose their community’s work including environmental, economic and social concerns in order to assure the full conservation of the site. They are well trained by SPNL on communication, adaptive management, social media, business planning, event management, water management, sustainable agriculture, and monitoring of wildlife.

The IBBA comprises a section of the Anti-Lebanon mountain ranges located on the eastern side of the village, as well as surrounding agricultural flat plains, forests, and wetlands. Anjar Wetland lies on one of the most important flyways in the world for migratory birds (part of the Great Rift Valley), where over 2,6 billion birds pass twice annually over Lebanon during their migration between Europe and Africa (Lebanon Traveler, 2015). Over 10% of these birds are water birds that depend on the marshlands for their survival. Several globally, regionally or nationally threatened bird species have been recorded in this IBBA, such as Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus (EN) (Figure 4), Pallid harrier (Circus macrourus (NT), Imperial eagle (Aquila heliaca (VU)), Greater spotted eagle (Clanga clanga (VU), Saker falcon (Falco cherrug) (EN), Turtle dove (Streptopelia turtur) (VU) and Syrian serin (Serinus syriacus (VU). The latest is a restricted-range species and Anjar holds the most significant breeding populations of the species in its range (Ramadan-Jaradi & Serhal, 2016). Anjar also supports the second population of Penduline tit (Remiz pendulinus) of Lebanon (Ramadan-Jaradi, 2014).

Figure 4: Egyptian Vulture (Source: Fouad Itani).

Among the globally threatened plant species, one could mention Tanner’s sumac (Rhus coraria) (VU) Schweinfurth’s buttercup (Ranunculus schweinfurthii) (EN) and Oak-like lycochloa (Lycochloa avinacea) (Nationally EN).

Among other significant wildlife species, we could mention the Turkish red damselfly (Ceriagrion georgifreyi) (EN). The wetland also supports the River otter (Lutra lutra) (NT), and Anjar represents its last remaining refuge in Lebanon, the Jungle cat (Felis chaus) and the Wild cat (Felis silvestris), both nationally threatened (Ramadan Jaradi, in prep.).

Activities developed by the Homat Al-Hima in relation with the natural heritage of Anjar include:

- Contributing to the planning management and adaptive management through the collection of scientific information related to nature.

- Contributing to the monitoring of the priority species: threatened, endemic, highly range restricted species.

- Accompanying the scientific researchers during their field studies to guide them and benefit from them.

- Guiding visitors on trails or with kayaks, raising awareness, cleaning site activities, etc.

- Participating in events concerning eco-tourism promotion, and nature interpretation.

- Leading on the organization of nature festivals, children’s educational summer camps, open days in the village, cleanup campaigns, etc.

- Conserving water through wise use, and wildlife through in-situ and ex-situ conservation as well as through bio-farming and law enforcement regarding poaching, sustainability of resources, protection of endemic and economically important species, etc.

- Protecting the habitat of the Syrian serin and ensuring its feeding areas within archaeological sites.

- Improving the implementation of a participatory reforestation plan in coordination with The Association for Forests, Development and Conservation (AFDC), the Municipality and the local community.

Cultural values

Although many himas in Lebanon have cultural and religious significance, Hima Anjar is a good example of the harmonization of the cultural heritage with the conservation of nature because it includes, beside the natural heritage, the Islamic Anjar Castle, an UNESCO Cultural World Heritage Site.

As per UNESCO (loc. cit.): “The ruins reveal a very regular layout, reminiscent of the palace-cities of ancient times, and are a unique testimony to city planning under the Umayyads”.

“The town of Anjar was established during the period Umayyad Caliph Al-Walid Ibn Abd Al-Malak (705-715) as a palace-city. Its name comes from the Arabic Ayn Al-Jaar (fountain from the rock) referring to the streams that flow from the nearby mountains. The ancient Anjar is an example of an inland commercial trading city at the crossroad of important routes. Built from scratch by the Umayyads, it used classic Roman design, a square walled city with four towers and gates” (UNESCO, loc. cit.). “At its peak, it housed more than 600 shops, Roman-style baths, two palaces and a mosque” (http://www.tracyanddale.50megs.com/anjaar/anjaar.html#). The town was never completed, and enjoyed a brief existence. “In 744, Caliph Ibrahim, son of Walid, was defeated and afterwards the partially destroyed city was abandoned. Therefore, the vestiges of the city of Anjar constitute a unique example of 8th century town planning, reflecting the transition from a Protobyzantine culture to the Islamic art and this through the evolution of construction techniques and architectonical and decorative elements that may be viewed in the different monuments” (Unesco loc. cit.).

After being abandoned for centuries, the area was resettled with several thousand Armenian refugees from the Musa Dagh (Mount Musa) area in 1939 (Asbarez, loc. cit.). When the French brought the Armenians to Anjar, they designed the urban land used with the shape of a flying eagle (Figure 5), where the Armenian Orthodox Church forms the head of the eagle representing the majority. Three small villages on each eagle’s wing are carrying the same names of the six villages in Mount Musa. The right wing carries the Catholic Church and the left the Protestant Church, which were numerically less important in the community. Thus, the memories of the Armenian refugees were transmitted in a meaningful way from Musa Dagh to Anjar.

Figure 5: Anjar Eagle and ruins. © Esri — Source: Esri, i-cubed, USDA, USGS, AEX, GeoEye, Getmapping, Aerogrid, IGN, IGP, UPR-EGP.

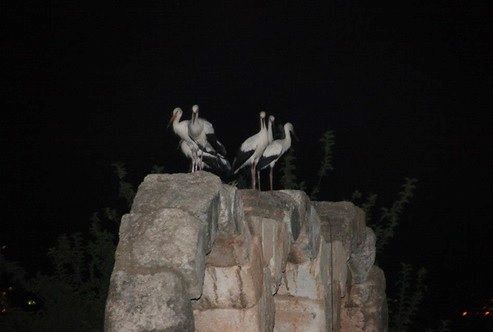

This explains why when a flock of 16 white storks, in 2015, was flying over Beqaa near Anjar and shooters began shooting at it, the survivors felt themselves safe and roosted on the monuments of Anjar (Figure 6). The municipality police in collaboration with the local community protected these white storks so as to continue their journey to their breeding areas in Armenia where they nest on chimneys of houses and locals are waiting for their return. Armenians from the local communities said that they protected the storks because they are refugees like them.

Figure 6: White storks found a refuge at Anjar in 2014 for roosting.

The cultural and spiritual significance of Hima Anjar refers to the values that local communities from different cultures and religions place on natural features that are meaningful and important to them. The members of the Armenian community arrived to Anjar as refugees in 1939. Their land where they were first settled was designed in a symbolic and meaningful way for them by their own leaders and professionals. Each religion group accepted the other in a hierarchy which takes in consideration not only their own adherents’ weight but also their spiritual attachment to Dagh Musa, resulting that they have always lived-in peace. This new spiritual connection brought them into contact with a reality greater than themselves, giving them meaning and vitality to their lives and motivated them to respect and care for the environment.

Although the Armenians of Anjar are distributed among Orthodox, Catholic, Evangelic and Protestant, they identify themselves as a united Armenian social group. They have been integrated to the new homeland and its spiritual and cultural values. Members of the local community and visitors alike look for inspiration in the beauty of the landscape; the charms of the island forest of Shamsine River, the rocks of the slopes of Anti-Lebanon, and the grazing areas. Silence, tranquility and beauty are intangible aspects of nature that are valued by all social groups.

The Directorate General of Antiquities is responsible for the Anjar ruins. The protection of the archaeological site is ensured through regular maintenance, including weeding and consolidation of the structures. The entrance is regulated and entrance fees are applied. A management plan was prepared in 2019 and implemented by the local community of Anjar, since then, with a funding support from MAVA. The expropriation of land parcels adjacent to the archaeological site will provide protection around the site and conservation of the beauty of the surrounding landscape (UNESCO, loc. cit.).

SPNL is the responsible NGO for the Hima/IBBA Anjar, including the archaeological site, due to the presence of 29 breeding bird species within its boundary, some of which are globally threatened, biome restricted or rare. Hence, the archaeological site is co-managed by SPNL and the Directorate General of Antiquities.

The activities developed by Homat Al-Hima in relation with the cultural heritage in Anjar include:

- Contributing to the planning and management of cultural values, tangible and intangible, through the collection of scientific, religious, ethnic, and spiritual information.

- Accompanying the scientists during their field research to guide them and benefit from them.

- Guiding visitors, monitoring the impact of cultural tourism on the ruins’ associated biodiversity, cleaning the archaeological site from the litter left by some visitors, etc.

- Being involved in events concerning cultural tourism promotion and interpretation activities related to traditions and cultural expressions associated with nature conservation.

- Leading on the organization of cultural festivals, children’s educational summer camps, open days, etc.

- Conserving the cultural properties with the support of the local authority and through the enforcement of the existing regulations.

The biodiversity is benefiting from both the protection of the archaeological sites and from the spirituality of the locals. For example, the birds of Anjar are stone dwelling species or species that use the top of stones to patrol their foraging area or to prey on creatures that use cracks of stones to hide. The Lesser kestrel (Falco naumanni) that was extinct from Lebanon, except from Anjar, regularly frequents the ruins to hunt on lizards that bask in the warm rays of sunlight (Ramadan-Jaradi, unpubl.). The globally threatened Syrian serin bird Serinus syriacus also benefits from the coniferous trees in which it nests, from the seeds of annuals grasses that grow between the pedestrian pavements and the spiders and other insects in the crevices of the old walls (Figure 7) that are included in its diet, and from the permanent access to water in the archaeological site where disturbance is minimal.

Figure 7: A female Syrien serin feeding on spiders in the crevices of the old walls of the ruins.

The Homat Al-Hima consider the Syrian serin their symbol (Ramadan-Jaradi, G., 2016), they are aware of the inter-relation between biodiversity and cultural sites and they intent to transmit this knowledge to visitors. Moreover, Homat Al-Hima act as a bridge of knowledge transfer between visitors and locals of Anjar.

Visitors aim at knowing the spirit of people and place through their historical and cultural heritage, including food. The food at Anjar is attractive and offered by several restaurants lying near water streams and farms of freshwater fishes.

Pressures and impacts

Tourism and agriculture are the main economic activities of Anjar. Clients of hotels and restaurants are attracted by the local gastronomy (delicacy and diversity of food) as well as by the generosity of the Armenian owners. The growing activities foreseen in the near future are eco, cultural and agricultural tourism. Even though, Homat Al-Hima prevents harmful impacts on natural and cultural environment. The rules within the archaeological site consist of leaving nothing on the site (e.g., trash) and taking nothing from the site. They also limit the passages to the existing trails. These rules prevent its deterioration and favor biodiversity protection from disturbance, pollution, legal hunting (not allowed within the site), and poaching. The whole land of Anjar has been subject to land use planning and building regulations since 1940, which have remained regularly improved till today. The local authority is enforcing land use regulations including planning, land use, subdivision, and non-conforming uses.

When the Armenian refugees were brought to Anjar, the area was an inhospitable terrain—rocky, swampy, and thorny, with scorching summers and freezing winters. Having no other choice, the Musa Daghians had to reconstruct their new community there. They stayed under tents for about one year until a French company built them houses and helped them purchasing fruit and ornamental trees. The area devoted to cereals cultivation in 1940 was ca. 400 hectares for wheat and 100 hectares for barley (Asbarez, Loc. cit.).

Much of the western flanks of the Anti-Lebanon mount chain within the area of Anjar and beyond were supporting woods and denser vegetation than the current status. During the years which the refugees were relying on wood as domestic fuel, wood cutting, conversion of forest into agricultural lands, and excessive grazing, led to a gradual loss of the forest cover. Nowadays, SPNL and the municipality of Anjar are involved in the restoration of the forest cover and its biodiversity in collaboration with AFDC and LRI to protect fragile soils, scenic beauty, as well as to preserve downstream water resources which feed the area.

In the past, the settlers in Anjar dried out swamps to eradicate malaria, and used them later to extend agricultural areas. However, currently the descendants of the settlers are aware of the principle of sustainability that is needed to ensure their livelihood and the lives of their children in a healthy environment.

The community’s long-term vision of Anjar has a sense of green stewardship. The Armenian refugees transformed Anjar into a lush green community. The local community understands that long term investment in green spaces and forests will leverage Anjar’s potential as a distinguished eco-touristic destination in the Anti-Lebanon mountain range able to accommodate activities such hiking, biking, rafting, or nature observation (AFDC and Anjar Municipality, undated).

Most of the prevailing economic activities of Anjar have positive impacts on the site conservation, including agricultural and forest activities. The reforestation with stone pine trees (Pinus pinea) is another economic activity aiming at producing pine nuts that are expected to generate a significant income in the near future. Cultural tourism to the Umayyad ruins and artifact shops near its entrance are also part of the economic activities. Eco-tourism involves observing biodiversity (mostly birdwatching through hiking trails, boats, camping etc.

The only economic activities that negatively affect the site are the drainage of some private lands to expand agricultural areas and the construction of hotels and restaurants, which may cause loss of habitat and pollution. For this reason, modern restaurants are located at the periphery of Anjar. The garbage generated by some tourists is regularly cleaned by the municipality of Anjar.

In the near past, there was a conflict between the otter (Lutra lutra) (Figure 8) and the aqua-culturists of one restaurant because of its raids on the trouts in the breeding ponds. However, after the establishment of the Hima Anjar, the increased number of the otter-watchers pleased the restaurant owners who changed attitudes, and started dealing with this species in a friendly way, offering the otter food, so as to appear and attract more visitors (Ramadan-Jaradi et al., 2019).

Figure 8: An Otter from Anjar (Source: Berj Tumberjian)

Hotels and restaurants do not seem to have negative impacts on the spiritual and cultural aspects of the site. However, some spiritual and cultural aspects may be negatively impacted by both tourists ignoring the trails and behaving with little respect towards the fragile ruins. Finally, some visitors may use disturbing loud speakers for dancing in open areas where the silence, tranquility and scenic views are shared spiritual values. SPNL is preparing a plan to increase the awareness of visitors to conserve the cultural and spiritual heritage, as well as building some additional facilities

At Anjar, conservation of the natural heritage and the protection of spiritual and cultural values are apparently complementing each other. Within the archaeological site, the protection offers an undisturbed haven to the at least six priority bird species. The conservation of the natural heritage is somehow supportive to the protection of the spiritual and cultural protection and vice versa. Only the use of herbicides on the trails within the archaeological site deprives the Syrian serin bird from the seeds of his preferred plants (Ghassan Ramadan-Jaradi, pers. obs.). Early 2020, one of us (GR-J) discussed this subject that threatens the Syrian Serin at Anjar with the mayor of the town. The latter thankfully instructed the concerned people to stop using herbicides in the area where the Syrian serin do breed, and to coordinate with Homat Al Hima in order to do the job of clearing the pedestrian path by hand.

Since 2004, SPNL has been working on the sustainable management of the wetlands, through the Hima community-based approach. Accordingly, management plans for sustaining biodiversity and empowering livelihoods were developed for the site. Eco-tourism has been promoted as a means to empower local communities and highlight the aesthetic, biodiversity and cultural values of the area. Several ecotourism facilities have been developed including a visitor’s center, picnic area, camp-site, natural hiking trails, birdwatching sessions, and rafting with kayaks.

The municipality is the local authority that is holding the reins and coordinating with the Internal Security Forces to deter poaching and irregularities on the site. The Armenian political party and the local community are very close and very supportive to their elected municipal council members.

Conservation perspectives and sustainability

The project “Restoring Hima Ecosystem functions though promoting sustainable community -based water management systems” in the Anjar and Kfar Zabad IBBAs, supported by the MAVA foundation, started on January 2013. The area included both Anjar and neighboring Kfar Zabad himas aiming to improving the water management irrigation systems and raising the capacities of farmers about sustainable irrigation practices in both sites. A water policy for the Anjar Water Users Association (WUA) was developed through participatory workshops. The project aims to restore Hima ecosystem functions through promoting sustainable community-based water management systems.

Another project focused on transferring the traditional experience of the Anjar Water Users Association is the management of water for agricultural purposes through the traditional open canal system to Kfar Zabad farmers to promote good governance and wise use of water for people and nature.

In Lebanon, the cultural heritage is protected by law. This law is firmly applied at Anjar since the discovery of the Anjar archaeological ruins. The protection is guaranteed by the Ministry of Culture through the municipality of Anjar, although the Department of Urban Planning is also involved.

Preservation of the intangible cultural heritage, including ideas, memories, knowledge, skills, creativity, spirituality, traditions, and other intangible values in conjunction with the places they are associated with Dagh Musa and its six villages has been very effective. Memories of the land of origin have made the refugees dedicated to the conservation of the new land. In the past, they purchased fruit trees and cultivated wheat and barley not only to survive but also to remember their homeland of origin. Today, the same memories and traditions have led the descendants of Armenian refugees to enage with reforestation plans that are supported by SPNL and AFDC. Similarly, the protection of the white storks was triggered by their memories of the fact that these birds could be on their way to breed in Armenia.

Before the middle of the last century, the refugees tended to Umayyad ruins that were neglected at the time, and they dusted, cared for, and protected the ruins from intruders. In return, the government allowed them to manage the ruins site and benefit from the income generated by tourism. As for visitors, they are of all religions, as is the case with tourism in other countries. In 2008, the SPNL declared Anjar, through BirdLife Internation, an Important Bird Area (IBBA) (BirdLife, 2022) and a Hima declared the Anjar municipality. Subsequently, SPNL reached an agreement with the inhabitants of Anjar to implement the principle of the Hema as community-based management of the IBBA. Consequently, the whole community of Anjar is nowadays involved in the management of Anjar and its natural and cultural heritage, especially after being trained on the management of the Hima and helped through by SPNL through projects funded from abroad by international organizations and donors.

Heritage conservation is an evolving practice, and one of the current trends focuses on identifying and recovering the connections between nature and culture. This approach has become instrumental for the interpretation, conservation and sustainable management of both natural and cultural heritage sites. At Anjar the cultural heritage is linked to the lives of communities and is fully integrated into the social, economic and environmental processes, making it an integral part of people’s daily experience. Subsequently, any effort aiming at protecting the environment and improving the social and economic wellbeing of local communities should consider their cultural and spiritual heritage. The cultural and spiritual values may offer a remedy when an action is inappropriately used, because both contribute to generate incomes from responsible eco-tourism through a balanced development in the area. For this reason, when some thought of building a restaurant within the forest, the Homat Al-Hima immediately reacted to this idea by emphasizing the importance of the forest in inspiration, tranquility, reflection and comfort.

Recommendations

Assuming that cultural and natural heritage are mutually supportive in this case, we pledge to work with faiths in ensuring that when Hima or IBBAs overlap with sites of cultural values, both natural and cultural/spiritual values will be considered. Hence, we recommend to:

- Update the management plan in order for the faith groups and conservation organizations to fully benefit from working together through the appreciation of the natural values that are indicated in the management plan, a matter that provides inspiration to so many.

- Strengthen eco-cultural tourism to benefit from the current positive attitudes of the visitors and the local community about the natural and cultural heritage. Especially, the adequate preservation of cultural heritage is not obtained if the tourism is perceived negatively by the local community.

- Organize activities involving local people in sustainable cultural tourism activities in order to create synergy and increase popularity for cultural value preservation.

- Conduct a workshop to list categories of natural, spiritual and cultural heritage to build upon them to emphasize conservation and protection of the values of the site.

- Develop project proposals aiming at improving synergy and collaboration among authorities for natural heritage and spiritual and cultural heritage protection to be submitted to interested donors.

- Increase awareness about the impact of visitors’ behavior or inappropriate conduct in the integrity and quality of the natural and cultural heritage.

References

AFDC & Anjar Municipality (undated). Participatory reforestation plan at Anjar.

Asbarez (2015). Armenian News. The Settlement of Musa Dagh Armenians in Anjar, Lebanon, 1939-1941.

Asia/Pacific Cultural Centre for UNESCO (ACCU), (2008), Country report: South Africa. Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage in South Africa.

https://www.accu.or.jp/ich/en/training/country_report_pdf/country_report_southafrica.pdf

BirdLife (2008). Datazone-Hima Anjar-Kfarzabad IBA.

http://datazone.birdlife.org/site/factsheet/hima-anjar–kfar-zabad-iba-lebanon

Retrieved on 7/12/2020

BirdLife RedList (2020a)- European Turtle Dove:

Retrieved on 8/12/2020

BirdLife RedList (2020b)- Syrian Serin:

http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/22720053

Retrieved on 8/12/2020

BirdLife International (2022) Important Bird Areas factsheet: Hima Anjar – Kfar Zabad. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 12/01/2022.

Information Ramsar Sheet (unpubl.) Report to Ramsar Secretariat submitted in 2017 by SPNL to declare Anjar a Ramsar Site.

IUCN (2012), Motion 122. Promoting and supporting community resource management and conservation as a foundation for sustainable development. Adopted at the 5th IUCN Congress, Jeju, Republic of Korea, Sept. 2012

https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/WCC-5th-005.pdf.

Gari Lutfallah (2006). Ecology in Muslim Heritage: A History of the Hima Conservation System. Environment and History (The White Horse Press, Cambridge, UK), vol. 12, No. 2.

Lebanon Traveler (2015), The Journey South.

http://www.lebanontraveler.com/en/magazine/lebanon-traveler-the-journey-south/

Ramadan-Jaradi, G., T. Bara, and Ramadan-Jaradi, M. (2008) Revised checklist of the birds of Lebanon 1999-2007. Sandgrouse 30 (1): 22-69.

Ramadan-Jaradi, G. (2014), Hima Anjar, a wildlife sanctuary and refuge to the Eurasian Penduline Tit, Remiz pendelinus in Lebanon. SPNL, Beirut-Lebanon.

http://www.spnl.org/hima-anjar-a-refuge-to-the-eurasian-penduline-tit/

Ramadan-Jaradi, G., Serhal, A. & Ramadan-Jaradi, M (2016) First confirmed breeding of the European Serin Serinus serinus in Lebanon. A potential threat to Lebanese breeding Syrian Serins Serinus syriacus? Sandgrouse 38 (1).

Ramadan-Jaradi, G. (2016), Impact of conservation efforts on the Syrian Serin at Hima Anjar. Report. SPNL. Beirut-Lebanon.

http://www.spnl.org/impact-of-conservation-efforts-on-the-syrian-serin-at-hima-anjar/

Ramadan-Jaradi, G., A. Serhal & B. Khatib (2019) Towards a cooperation between the Eurasian Otter Lutra lutra and local people of Hima Anjar/Kfarzabad, Lebanon: A case study. OTTER, Journal of the International Otter Survival Fund 2019, 26-29.

Ramadan-Jaradi, G., F. Itani, J. Hogg, A. Serhal, & Ramadan-Jaradi, M. (2020) Updated checklist of the birds of Lebanon, with notes on four new breeding species in spring 2020. Sandgrouse 42 (2): 186-238.

Serhal, A., Khatib, B., Jawhary, D., Khatib, T. and Farah, N. (2010), The involvement of Local Conservation Groups in IBA conservation in the Himas of Lebanon. Report. SPNL. March, 2010.

http://www.birdlife.org/sites/default/files/attachments/Review-of-LCGs-in-LEBANON_Final.pdf

Serhal, A. (2016), Homat Al Hima Guideline Manual. Report-publication. SPNL. Beirut-Lebanon. http://www.spnl.org/homat-al-hima-guideline-manual/

SPNL (2012), Regional Progress in Hima Revival. Report. SPNL, October 2012. Beirut. http://www.spnl.org/hima/

UNESCO (2018), World heritage list/ 293.

https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/293 Retrieved 2018.